A NEW PARADIGM FOR CELEBRATING

THE LINKS, LIFE, AND LEGACY, BUILT

ON GOLF EQUITY AND INCLUSION.

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER

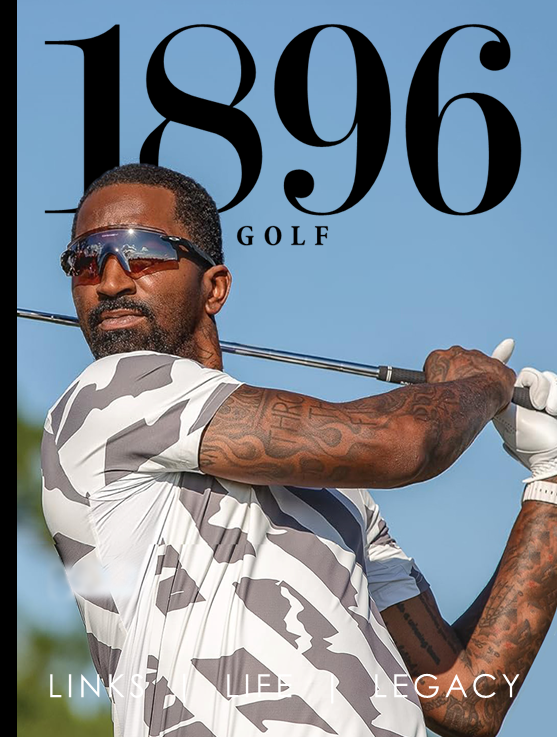

Join Our Community and Receive Updates on the Groundbreaking Launch of the 1896 GOLF MAGAZINE

and the Inclusive 1896 Golf Club.

Be among the first to receive exciting news, exclusive invitations, and inspiring content directly in your inbox.

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER

Join Our Community and Receive Updates on the Groundbreaking Launch of the 1896 GOLF MAGAZINE and the Inclusive 1896 Golf Club.

Be among the first to receive exciting news, exclusive invitations, and inspiring content directly in your inbox.

LINKS.

We uncover the essence of golf through iconic courses, cutting-edge architecture, and the latest equipment and gear.

LIFE.

Experience immersive content in the vibrant lifestyle and culture surrounding golf, with player interviews and features on fashion, travel, and community.

LEGACY.

Looking back at golf’s rich heritage, we delve into the trailblazing Black figures who paved the way and their impact on society and golf culture.

1896 GOLF is a pioneering multimedia platform and lifestyle brand dedicated to reshaping and amplifying the narrative for Black golfers and People of Color, inspiring a new and informed generation of players. We pay homage to the sport’s unsung heroes and embrace the diverse tapestry of modern golf culture, championing an inclusive future for all. Sign up for exciting news and updates on our upcoming inaugural print magazine launch, and join our community.

TO EXPLORE OPPORTUNITIES TO PARTNER WITH 1896

GOLF, PLEASE CONTACT DANDRE@1896GOLF.COM